Canada’s still untapped aquaculture potential

November 20, 2020

By

Liza Mayer

Exec sees a greater role for indigenous people in farmed salmon industry’s future

Photo: Cermaq Canada

Photo: Cermaq Canada Canada is just skimming the surface when it comes to utilizing its coastline that’s viable for aquaculture. That could, and should, change, said the head of the Canadian Aquaculture Industry Alliance (CAIA).

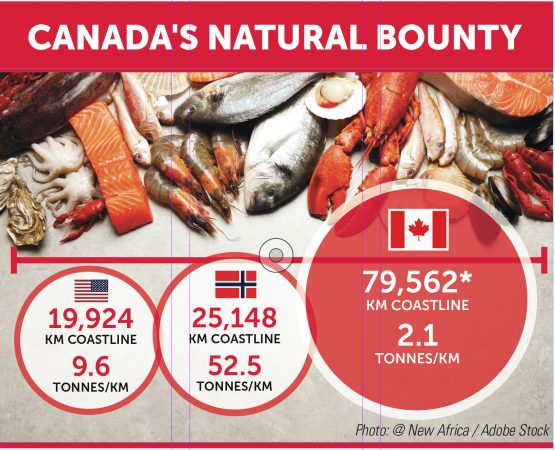

Canada produces 2.1 tonnes per kilometer of farmable coastline. In comparison, Norway produces 52.5 tonnes per kilometer, and the United States, 9.6 tonnes. (see infographic).

The figures show how Canada, which has a much longer farmable coastline than the two countries, hasn’t come close to realizing the opportunities in aquaculture despite the clear positive impact the industry has on local communities, said Tim Kennedy, president and CEO of CAIA.

“We have not seized the opportunity in Canada for sustainable aquaculture of all types,” Kennedy told participants at the 5th Indigenous Resource Opportunities in October, a First Nations-led virtual conference focused on sharing success stories of BC’s indigenous communities.

Canada is now the eighth largest volume producer of seafood in the world. The goal is to become the top three sustainable fish and seafood producer by 2040, said Kennedy. That goal is enshrined in the recently released Canada’s Blue Economy Strategy 2040, a roadmap CAIA developed with its wild-capture counterpart, the Fisheries Council of Canada.

*Data: RIAS Inc. (2014) Canada’s Aquaculture Industry: Potential production Growth and Footprint. *Only considers provinces with marine coastline suitable for aquaculture (excludes all three Prairie provinces, Ontarioo, and Canada three territories). Photo: @ New Africa / Adobe Stock

The pandemic has only heightened the industry’s important role and the opportunities to participate in it, said Kennedy. He noted that 70 percent of the seafood Canadians consume is imported and only 30 percent is local supply.

Kennedy believes “there’s a huge opportunity for indigenous partners to recognize that need and to look at branding product in very special ways,” such as, perhaps, branding farmed Atlantic salmon from BC as “Reconciliation Salmon,” he suggested.

“Let’s have a vision that we can all get behind,” said Kennedy as regards the 2040 goal. “We think this is something that we can work on… on measurability, on metrics. And we think that we should and can be the very best producer of top quality seafood in the world. That’s our vision and we’d really enjoin others to join us in that partnership.”

First Nation’s role

Conference chair, host, and president of the Nanwakolas Council, Dallas Smith, acknowledged the evolving relationship between the farmed salmon industry and the First Nations in whose territories salmon farms are sited. His First Nations community has a partnership with Grieg Seafood BC.

‘We have not seized the opportunity in Canada for sustainable aquaculture of all types,’ says Tim Kennedy, head of the Canadian Aquaculture Industry Alliance

“It’s nice we’re not just thought of as a landholder (of farm sites) you’ve got to pay rent to, but that there’s actual training opportunities that are developed to get our people meaningfully involved,” said Smith.

But he also noted the need for “meaningful jobs” – not just manual labor – for indigenous people that would allow them to move up the ladder and “build a career that’s really going to support their families.”

Kennedy acknowledged this continues to be a challenge but the industry’s relationship with First Nations is evolving in important ways, he said. This includes hiring indigenous people at entry level and training them “so we’re seeing management-level partnerships. There’s more to do, there’s no question about it, but I know that the companies are committed to that.”

At Grieg Seafood BC, indigenous employees work as farm managers, farm technicians, in hatchery maintenance, and as operations specialists, said Marilyn Hutchinson, the company’s director of Indigenous & Community Relations.

“Like the other BC farming companies, we work with colleges and universities to facilitate the training required to support their successful employment,” Hutchinson said.

She added that there are opportunities to contract out some services with indigenous-owned businesses, such as water taxi services, barging, meal catering and environmental monitoring. All of these “support a nation’s own goals for economic self-sustainability,” she said. “The more we contract with indigenous companies, the greater their financial capacity to grow and provide other services to our sector.”

Hutchinson sees a future where indigenous involvement in the farmed salmon industry would be greater. “I know there will be indigenous ownership of salmon farms, or shared ownership, or sub licensing or joint ventures – one of many different mechanisms that will see our indigenous partners leading the growth of aquaculture in BC. It has already started but the pace of this change is accelerating because the leaders are asking for it to happen now,” she said.

Already, there are aquaculture businesses where First Nations are more than just the landowners, but owners and custodians of the businesses. One of these is Coastal Shellfish Corp, a business in Prince Rupert, BC, that’s 95-percent owned by First Nations. It is the only commercial scallop hatchery operating in North America today, and represents $25-million in indigenous investment since 2003.